“One of the few subjects on which we all seem to agree is the need for justice. But our agreement is only seeming because we mean such different things by the same word. Whatever moral principle each of us believes in, we call justice, so we are only talking in a circle when we say that we advocate justice, unless we specify just what conception of justice we have in mind. This is especially so today, when so many advocate what they call "social justice"—often with great passion, but with no definition. All justice is inherently social. Can someone on a desert island be either just or unjust?” (Sowell 1999, 3)

What does the word “justice” mean to you?

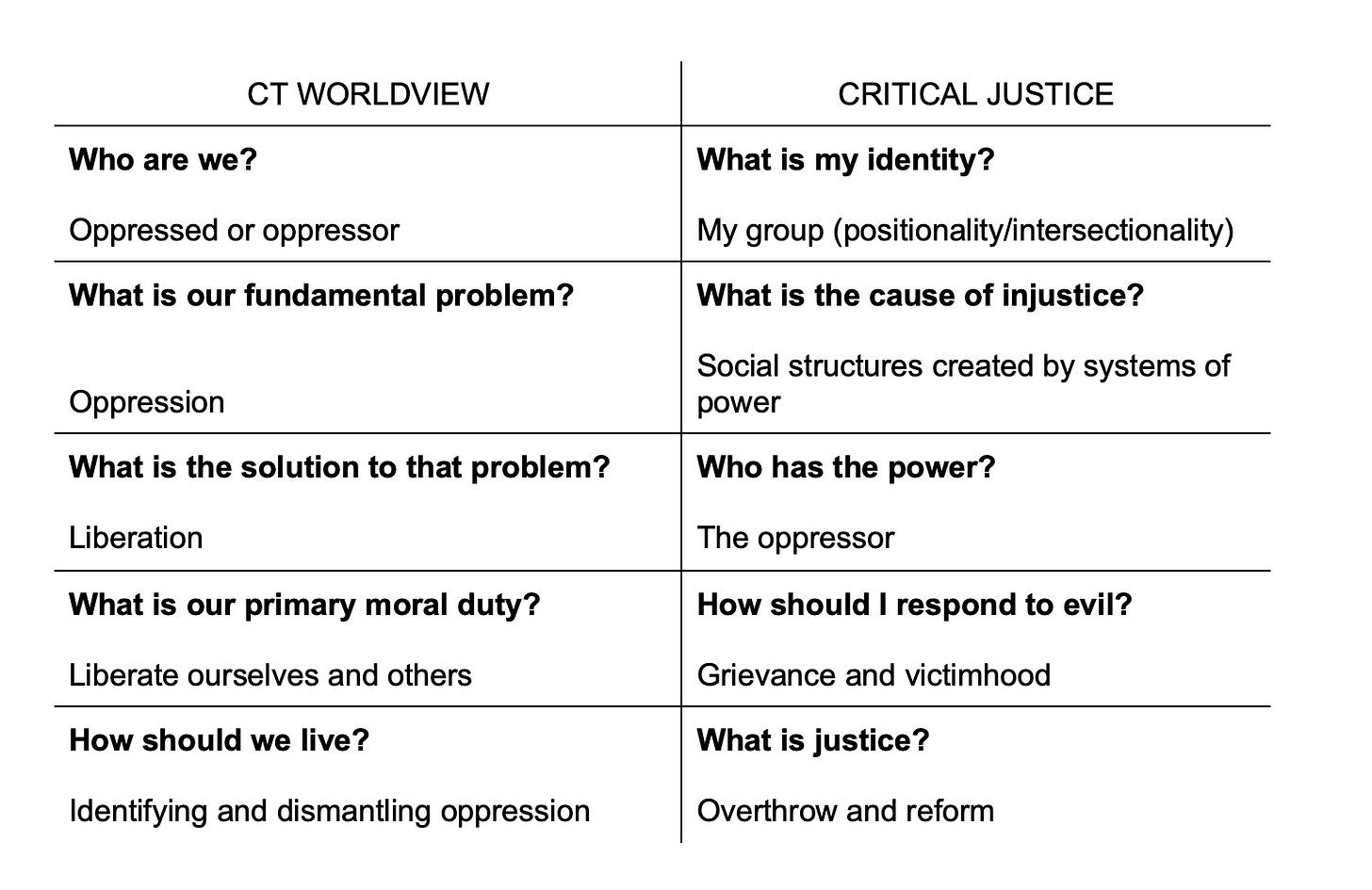

Let’s go back to what Socrates teaches, establishing definitions, and determine what we mean by justice. As Thomas Sowell states, all justice is inherently social. Justice is not an individual pursuit. The quest for justice is something we do for the sake of both ourselves and others. Our concept of justice is created by, and anchored to, our worldview. How can we identify our approach to justice based on our worldview? Here are some clarifying questions about how to relate justice to the worldview we adopt.

In the book Is Everyone Really Equal? An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education, Sensoy and DiAngelo define justice this way.

Critical social justice recognizes inequality as deeply embedded in the fabric of society (i.e., as structural), and actively seeks to change this.

The definition we apply is rooted in a critical theoretical approach.

All people are individuals, but they are also members of social groups.

These social groups are valued unequally in society.

Social groups that are valued more highly have greater access to the resources of a society.

Social injustice is real, exists today, and results in unequal access to resources between groups of people.

Those who claim to be for social justice must be engaged in self-reflection about their own socialization into these groups (their “positionality”) and must strategically act from that awareness in ways that challenge social injustice.

This action requires a commitment to an ongoing and lifelong process.

(Sensoy & DiAngelo 2017, xx-xxi)

Sensoy and DiAngelo make it plain that their definition of justice is rooted in Critical Theory. What does the worldview of CT say? Fundamentally, the world is divided into two groups: oppressed and oppressors. Both the definition of justice and the worldview underlying it assert that this division is deeply ingrained in the fabric of all society. Not just America. Not just developed nations. The whole world works this way.

Although we are individuals, CT and critical justice state that the main definition of our identity is the groups we belong to. We must engage in self-reflection about what groups we belong to and act based on that awareness. This is called positionality.

Readers might wonder how to engage with positionality. In other words, how can we know what groups we belong to? To figure this out, we should first understand another concept being alluded to here, that of intersectionality. Intersectionality is defined this way in the Encyclopedia of Diversity and Social Justice:

Our experiences of the social world are shaped by our ethnicity, race, social class, gender identity, sexual orientation, and numerous other facets of social stratification. Some social locations afford privilege (e.g., being white) while others are oppressive (e.g., being poor). These various aspects of social inequality do not operate independently of each other; they interact to create interrelated systems of oppression and domination. The concept of intersectionality refers to how these various aspects of social location “intersect” to mutually constitute individuals’ lived experiences. The term itself was introduced by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989, although intersectional understandings of the social world precede her work. (Thompson 2015, 435)

Crenshaw first used the term in a paper published in the University of Chicago Legal Forum titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex.” The concept of intersectionality says that all our experiences in life are shaped by the groups that we belong to and those groups’ relationship relative to privilege or oppression. Through our intersectionality, we can learn our positionality.

Positionality is the concept that our perspectives are based on our place in society. Positionality recognizes that where you stand in relation to others shapes what you can see and understand. For example, if I am considered to be an able-bodied person, my position in a society that devalues people with disabilities limits my understanding of the barriers that people with disabilities face. I simply won’t see these barriers, in large part because I don’t have to – society is structured to accommodate the way I use my body. (Sensoy & DiAngelo 2017, 15)

I’m not attempting to overwhelm you with terminology, but we must understand these terms and their definitions to accurately define how different worldviews see justice. Positionality is our position in society based on our intersectionality – our relationship to oppression. Positionality is of vital importance to the worldview of Critical Theory. Through positionality, we must understand that by default we devalue other people who are in a “lesser” position.

In light of this, let’s look at justice. The first question we can ask regarding a worldview’s definition of justice is “What is my personal identity?”

As we learn about intersectionality and positionality, we will see that CT teaches us that the most important thing about our identity is the social groups we happen to belong to. Our personal history, life experiences, choices and deeply held beliefs are secondary to these groups.

CT argues that identity must be defined in two ways:

Intersectionality – my group’s experiences as oppressive or oppressed.

Positionality – where my group is relative to oppression.

CT doesn’t deny that people are individuals, but the primary way of defining our identity is group membership. How can we know what social groups exist, which ones we belong to, and whether they are oppressive? DiAngelo and Sensoy give us a good starting point on page 64 of Is Everyone Really Equal?

Critical theorists will tell us these aren’t the only groups that exist; these are just examples for us to work on. Because truth is subjective, most critical theorists – Sensoy and DiAngelo included – say that we must also self-define our groups relative to who we perceive to be oppressive. We can create groups to further refine our positionality. Since Critical Theory teaches that truth is subjective, the truth of what a “group” is or isn’t must also be subjective.

How about intersectionality, our group’s relationship to oppression? InTeaching for Diversity and Social Justice, the authors provide a matrix for us to further explore our intersectionality

Why is this important? First, let’s look at the position of an oppressor. Whenever we find ourselves in the dominant/oppressor group, we must “engage positionality.” In this theory, we should realize how the groups we belong to are oppressive throughout society and how they contribute to systemic oppression. If we are in an oppressor group, we are also incapable of understanding the experiences of those in an oppressed group.

How does this work in the real world? Let’s say that you were raised in a working-class family. Your parents may have struggled to put food on the table, and you may not have been able to afford college. Imagine that you worked hard in school and earned a four-year scholarship to college, started a business, and became a multimillionaire. The critical approach to justice would say that you now belong to a dominant or oppressor group. You are now mostly incapable of understanding the experiences of working-class families, even though you came from one. Your primary identity is not your experiences or life journey; it's your group. At one point, you may have faced oppression. But now that you are no longer oppressed, you are an oppressor and are contributing to a systemic economic and social problem. You should engage positionality and understand where you oppress the working class. Just by your membership in a “wealthy” group, you are an oppressor.

Making a person’s main identity that of their groups is equivalent to making a worldview out of stereotyping. Primarily identifying all members of a group by their membership to that group – by choice or by birth – is Critical Theory’s preferred method of seeing society.

Now, let’s look at the position of someone who is oppressed. A person who belongs to an oppressed group must be able to identify and articulate how they have been victimized by the groups that oppress them. There are infinite ways for a person who is oppressed to define their oppression.

You may not be a Christian. If you aren’t, it means you are in an oppressed religious group. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice talks specifically about religious oppression in America and the Western world. “The significance of Christianity in U.S. life and the challenges it poses for minority religions is a social justice issue that requires the kind of historical knowledge and structural/cultural analysis we use to understand other forms of oppression that stand in the way of social justice” (Adams & Bell 2016, 255).

According to Critical Theory and critical justice, the influence of Christianity must be subject to the same analysis as racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice. The book goes on to define the ways that Christians enjoy “Christian privilege,” including the Christian practice of evangelism:

“Non-Christians, whether adherents of other faith traditions or agnostics and atheists, are subject to the proselytizing encouraged in evangelical Christian practice. Christians who believe they are doing the "right thing" by carrying the "good news" to non-Christians would be shocked to know that such proselytizing can be experienced as bullying and harassment--and that when repeated, build up on a daily basis as microaggressions that cause anxiety and fear.”(Adams & Bell 2016, 255)

As an example, one of the primary ways that many Christians continue to practice systemic oppression is through the pro-life movement, according to Adams and Bell. Critical theorists frequently assert that to oppose the pro-choice movement, or denounce abortion as immoral is discrimination, prejudice and oppression.

Our definition of justice is just as important as our commitment to justice. And we are barely scratching the surface of the amount of work that has been done related to the definition of justice. There are academic areas of study related to researching privilege, oppression, intersectionality, positionality and justice across every group that can be identified. Many of these are known as grievance studies, where scholars can study how groups have been oppressed. Anywhere one can identify oppression is an opportunity to undertake grievance studies to understand a victim’s positionality and intersectionality.

Grievance studies include but aren’t limited to:

Race

Class

Gender

Sexuality

Religion

Able-bodied vs. Disabled

Fat

Immigrant

Indigenous

This can seem overwhelming. The reason I draw all of this out is to show that in critical justice, we don’t find ourselves with just one level of positionality—for instance, our race. We also have a certain socioeconomic status, some form of gender expression, nationality, education, marital status, occupation, sexuality, body shape, class, religious orientation and so on. Each of these things defines both our positionality and intersectionality. And our relationship to justice.

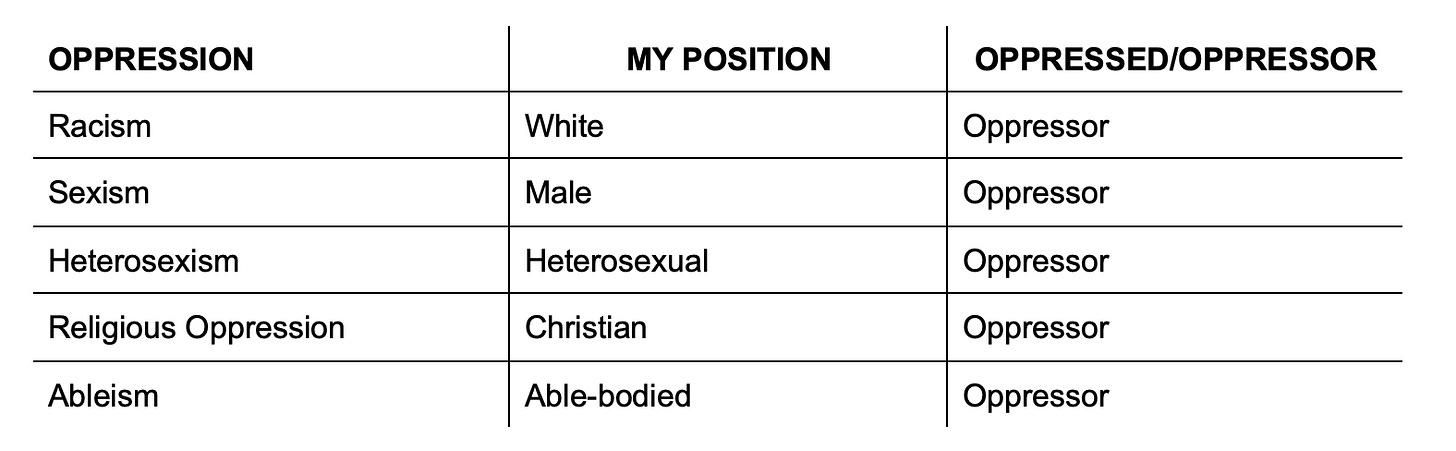

Intersectionality is a concept that equips us to define all the positions that we occupy, the layers of oppression that we may face. Let’s take a few of these and attempt an exercise to define our intersectionality

In every criterion we have listed here, I would qualify as an oppressor. Therefore, I must understand that I both create and perpetuate oppression, regardless of my intent. The groups I belong to have been defined as oppressive; therefore, I am an oppressor. Which means, according to critical justice that my very existence perpetuates injustice. My personal experiences, convictions or values are irrelevant.

Take a minute and take a look at your own positionality and intersectionality along these 5 lines.

Why is it important in critical justice to define our intersectionality? Because the more oppressed groups we belong to, the more we must strive for reform and overthrow of the dominant group: the oppressors. Our goal in practicing intersectionality is to find out where we are either oppressed or an oppressor through every permutation of groups we might belong to. This becomes extraordinarily complex almost instantaneously.

If you’re female or define your gender as something other than “male,” you must help to overthrow and/or reform the male power structure prevalent in society.

If you’re homosexual, you must help to overthrow and/or reform the heteronormative power structure.

If you’re not a Christian, you must ensure that Judeo-Christian ethics and practices are overthrown and/or reformed.

If you’re all three of these things at the same time, you have multiple levels of oppression that you must face. Someone who belongs to more oppressed groups could have much more than three levels of oppression. That’s why the matrix of intersectionality is so important.

In the world of CT, we must be able to define positionality and intersectionality. The only people worth listening to and capable of bringing about true change to society are those in the oppressed class. Anyone in the oppressor group is, has been and will always be a part of the problem. The oppressed are the only ones who can change the system, oppressors, at best, can become an ally to the oppressed as they overthrow the power structures of society.

Critical justice teaches us that if we feel oppressed, victimization should become a key part of our identity. We should then lament the grievances of our victimhood. The clearer we are about how we have been victimized, the clearer it becomes who and what we should overthrow and reform. Grievance and victimhood are the preferred tools of change and the chief ways by which we learn to liberate ourselves and others.

How do the worldview of Critical Theory and the concept of critical justice come together?